International Coastal Cleanup | 2012

The idyllic setting of Saint Martin’s makes it a favourite for vacationers, who prize the Island’s natural beauty and the feeling of isolation it provides. Located eight kilometers off Teknaf, in the Bay of Bengal, Saint Martin’s Island is one of the jewels in the country’s crown.

Bangladesh’s only present coral reef, expansive blue, crystal clear waters and uncountable coconut trees, makes the island our very own piece of the Caribbean heaven. However, its beauty is now threatened everyday.

Being a very small Island, only around nine kilometres, Saint Martin’s Island is facing new dangers everyday. Global Warming, rising sea levels, unchecked shell and coral collection and throngs of tourists are all factors which are slowly nudging the islands towards destruction. Locally known as Jinjira, the Land of Coconuts, it is quite alarming to know that even the number of coconuts have fallen drastically.

International Coastal Cleanup, St. Martins Island, Bangladesh 2012

The effect of carbon footprints is embedded on the Island, serving as a cautionary sign for now. However, if we don’t read the signs, it may be much too late. Whether the change has been wholly natural or a direct fault of our own is a point to ponder indeed, but for now it is more prudent to control the aspect which we can. And that’s exactly what was done on 9 November, 2012.

As part of the global International Coastal Cleanup movement, Coca-Cola sponsored the Bangladeshi chapter of the event, lending support to the non-profit organization, Kewkradong.

The International Coastal Cleanup started nearly 25 years ago in a bid to rid the oceans, beaches, lakes and rivers the world over of accumulated trash and debris. Soon spreading to over 152 countries, the cleanup has seen interest rising dramatically, culminating in 9 million volunteers cleaning over 145 million pounds of waste.

This has made it the largest volunteer for ocean health in the world. However, it isn’t only about garbage collection. Every item collected is meticulously listed and tracked. This data is then used by Ocean Conservancy, the world’s leading advocate for Oceans, to prepare an annual report on the state of the world’s ocean.

This has made it the largest volunteer for ocean health in the world. However, it isn’t only about garbage collection. Every item collected is meticulously listed and tracked. This data is then used by Ocean Conservancy, the world’s leading advocate for Oceans, to prepare an annual report on the state of the world’s ocean.

The reports are always shocking; in 2010 alone volunteers found 26,205 batteries among 8 million pounds of trash and debris. The numbers speak for themselves. Not only does the rubbish choke the lifelines of the rivers, it is also a disaster for the eco-system, with the plastic trapping and killing the turtles, the corals and harming the ocean life irreparably. Thus, every year the volunteers attempt to help the water-bodies.

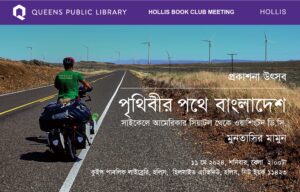

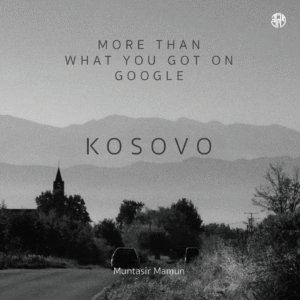

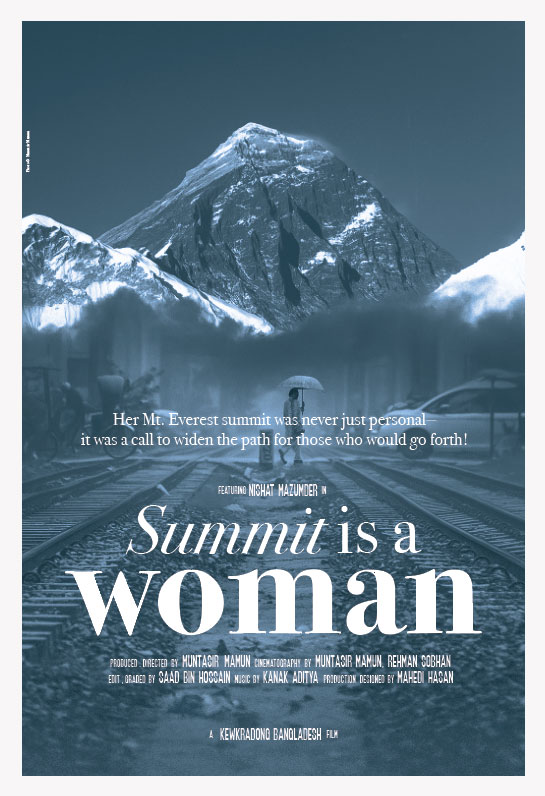

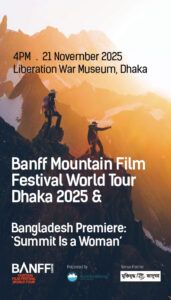

Muntasir Mamun, the notable journalist, and the figurehead of Kewkradong understands the insignificance of the number.

“I know that this once a year cleanup cannot make a huge difference, but it makes some difference. It helps spread awareness and it affects those who see and participate,” Mamun explains, enthusiastically. The adventurer and conservationist, Mamun’s Kewkradong brought the cleanup movement to Bangladesh nearly eight years ago and it has since been going strong.

“It started with a few members the first year, then a few hundred the next and now we have thousands,” he explains the hype the movement has generated in the growth. Citing the example of the Galapagos Island, Muntasir paints a stark picture of the future of Saint Martin’s Island. Thankfully though, organisations like Kewkradong are around to delay a disaster and perhaps do enough to prevent what now seems inevitable.

Although the organisation in question advocates the need for adventure by arranging numerous hiking, trekking, water sports, etc., it embraces the concepts of volunteerism, naturalism and eco-tourism, gathering enough nature lovers to send a strong enough message.

Thus on the fourth of November, dressed in the colours of Coca-Cola and with the message of conservation and cleanup, over a 100 volunteers from different parts of the country and almost 300 local students began the proceedings with much gusto.

Starting off, armed with bags and plastic gloves at eight in the morning, the volunteers worked till 12 pm. The local area Chairman arranged the students and watched over the proceedings. There was excitement in the air mingled with a sense of satisfaction. There was no leader nor any division that day, as all worked together as saviours of the sea.

The locals watched on at first and then began to take part as well. “How much will you be paid for this?” a curious local woman asked. When she was told this was voluntary work, she was surprised but pleased and she expressed her gratitude by inviting one of the volunteers for tea at her son’s stall.

Each and everyone went about their work, getting themselves dirty to clean up, as an old adage suggests. While some cleaned the beach, others busied themselves collecting the rubbish from the bazaar and surrounding areas. Soon, the time had come to tally up the results. Bags of garbage were piled together and the data collection began.

Ibrahim Khalil, a first year student from UIU, was taking part in the event for the first time and he provided some insights. “Although this was my first experience I believe it was a good one,” he summed up. “But in the future, I believe we need a bigger event. This was about awareness and we did raise some, because we even had some tourists helping us,” Khalil stated.

In a conference after the cleanup, Zach, a Surfing Tigers volunteer and ocean conservationist from Hawaii drew parallels and contrasted between his island and Saint Martin’s. “Hawaii is cleaner, despite the even larger number of tourists. That’s because we believe in sustainable living, giving back more than we take,” he explained. The discussions also criticised the worldwide packing standards for certain products, using plastic, a non-degradable.

The final tally revealed almost 300 kg of non-biodegradable rubbish, collected in less than 3 hours. Of this, plastic bags and cigarette butts were the biggest offenders. Of course, the bigger difference was in the people’s mental states, with most volunteers refraining from disposing of their waste everywhere, although this correspondent did notice others who did just what they preached not to do.

Overall though, the event wasn’t just about a day of cleaning the beach; it also highlighted other issues. Even though a crowd of easily 400-1200 tourists visit Saint Martin’s everyday, the island has no sewerage system and nor does it have any dumping grounds of trash collection agencies. So where does all that waste end up? Back in the oceans of course.

As organisations like Kewkradong the world over become our last saving grace, the beast behind the mighty of the blue water around Saint Martin’s rears itself. The Island recovered from a cyclone almost two decades ago and life continued as usual. It will survive again, rising from the depths it sinks to. The planet will continue to exist. Only one realisation holds true — the race isn’t to save Earth really; it’s to save mankind.

By Osama Rahman/ The Daily Star /2012/11/03